You might have heard the term ‘multi-barrier approach’ during discussions about geological disposal. But what is this, exactly?

The GDF developer, NWS, say that a combination of natural and man-made barriers will contain the waste in a GDF, and these work together to help safely isolate the radioactive waste.

Containment means keeping the waste where it is placed. Isolation means putting the waste away from people and the surface environment.

Liam Payne, Research Manager for NWS, said: “A GDF cannot be built and operated unless it can be robustly demonstrated to the regulators [the Environment Agency and Office for Nuclear Regulation] that it will be safe. The multi-barrier approach is key to demonstrating this long-term safety and it will be a key factor in how we characterise a site and then subsequently how we construct and operate the GDF so we know that it will remain safe and not cause harm to people and the environment”.

In a GDF, the waste will be isolated in sealed vaults and tunnels deep underground, between200m and 1,000m (656ft and 3,280ft) below the surface. The radioactive material is then contained while it decays naturally over time.

What goes into a GDF?

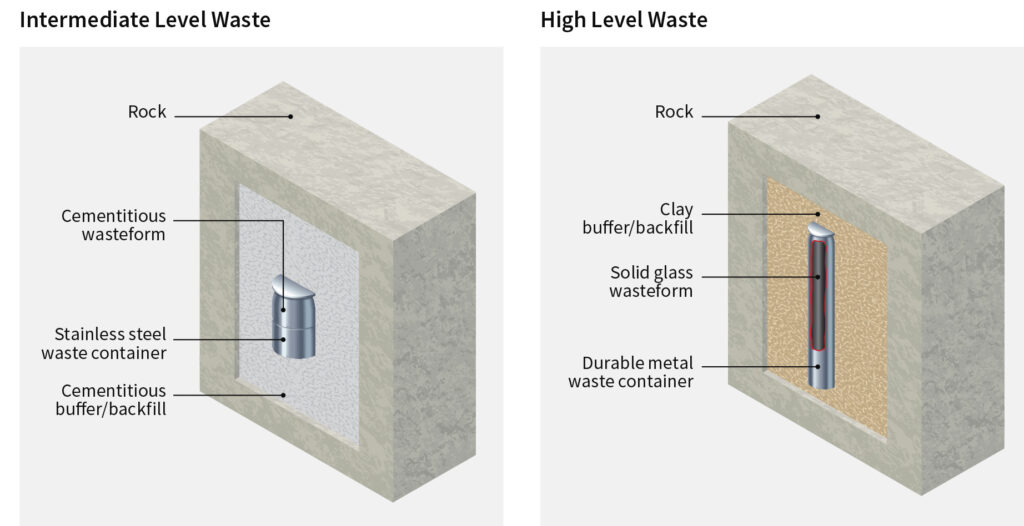

Only solid radioactive waste will go into a GDF. This makes it safer to handle, transport and dispose of. The solid waste is packaged into secure, engineered containers made from a durable material, typically copper, steel or concrete, depending on the type of waste and geology. The containers are designed to last anywhere between a few hundred years to tens of thousands of years, depending on the nature of the waste.

The radioactive waste containers will be placed in a GDF, surrounded by a protective backfill and buffer material.

This backfill of cement or clay prolongs the life of the containers and slows down the release of radioactivity. The final barrier is the natural barrier of several hundred metres of stable rock, preventing radioactivity from moving towards the surface when other barriers eventually degrade over the very long timescales.

Once complete, the GDF will provide safety without the need for further action. Together, these barriers are designed to provide multiple levels of protection from the waste for many thousands of years, all whilst the levels of radioactivity in the waste naturally declines.

How much waste goes into a GDF and where is it now?

Roughly 750,000m3 of packaged waste could be destined for a GDF. The legacy waste in the UK has been building up for more than 70years; most comes from the nuclear power generation, but it is also aby-product of many medical and industrial processes and research and defence activities that make use of radioactivity and radioactive matter.

While the waste is currently stored safely above ground, with the majority at Sellafield in Cumbria, this is not a sustainable or permanent solution. The stores need to be continually monitored to keep the waste secure and periodically refurbished while the radioactivity naturally decays.

For some of the waste this will take many thousands of years, so even if well maintained, eventually, the surface stores will need to be replaced, or the waste moved elsewhere. Surface storage will also be vulnerable events such as climate change and human conflict.

All waste destined for a GDF will be UK-owned. International law states that spent fuel and radioactive waste remain the ultimate responsibility of the country in which it was generated.

For more about the UK inventory visit ukinventory.nda.gov.uk